More than 3,000 migrants have died attempting to cross the Mediterranean in 2016, part of a wider catastrophe that has seen migrant deaths reach their highest ever recorded level this year. While the shipwrecks and drownings have made headlines globally, the violence and exploitation that occur on the long journey towards the coast often go unrecorded.

For their report Humanity at a Crossroads the Red Cross interviewed refugees and migrants in Italy, Egypt, Nigeria and Sudan about the routes they have taken towards Europe. The men and women described violence at every stage of the journey. Beatings, abuse, sexual violence and forced labour are common and many people have seen others die from hunger and thirst in their attempt to cross the Sahara desert. Nearly all of those interviewed had been detained at some point in their journey.

Conditions in Libya, where people wait in the hope of finding a way to cross to Italy, are particularly bad, with vulnerable and desperate migrants making easy prey for kidnappers and militias.

The movement of people across northern Africa is a mix of those fleeing conflict in countries like Eritrea and Somalia, and others trying to escape extreme poverty.

World leaders meet at the UN headquarters in New York today to try to find solutions for the refugee crisis, though negotiations before the summit failed to produce any concrete measures. On Tuesday Barack Obama hosts a summit on refugees with the UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon, and leaders of some of the countries deemed to have done most for refugees or carrying more than their share of the burden: Jordan, Mexico, Sweden, Germany, Canada and Ethiopia.

The Red Cross is calling for humanitarian assistance and protection for people travelling all along the migratory route to Italy, including the continuation of search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean.

Tessy, 19, Nigeria

Tessy arrived at the port of Catania in August 2016 with severe burns to her legs. During the sea journey from Libya to Italy, six people on her boat died. Tessy became covered in fuel which caused severe burns when it mixed with saltwater. She had to be taken to hospital as soon as she landed in Sicily, and received follow-up care after she was discharged from the Italian Red Cross health clinic.

Tessy took two attempts to get to Italy. During her initial journey, the boat in which she was travelling was intercepted and had to turn back to Libya, where she was imprisoned. Beatings and whippings were frequent, and food was scarce. There were ants in her room, and, ‘You would sleep with mad people,’ she says. Finally, she left again on another boat, which was rescued and reached Italy after three days.

Tessy’s journey to Italy from Nigeria took five months. She is from a family of seven children, and left her home because she wants to continue her education. Her dream is to study banking.

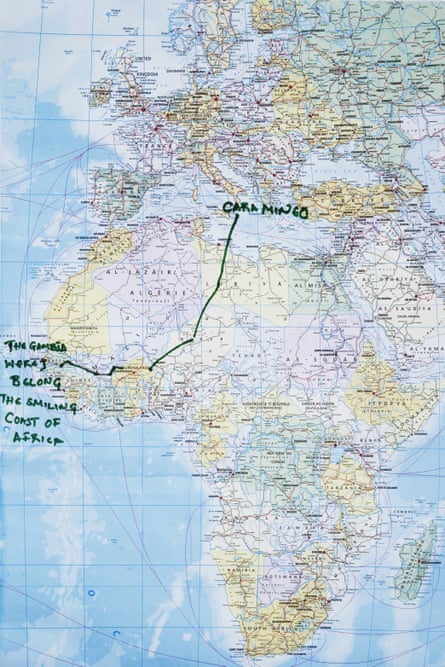

Musa*, 23, Gambia

Musa never intended to leave his country, but has lived in Sicily for three years, after arriving in Lampedusa in March 2013.

‘When my father died, that was when the main problem started,’ he says. His father’s second wife threw him out of his home, so he left Gambia for Senegal to find work to support himself.

In Senegal, he worked in construction, but his boss told him that there were better prospects in Libya. After three or four months, Musa followed his advice, but when he reached Libya, he ended up being imprisoned. ‘Libya is worse than hell. I spent one year [there], but I cannot tell you anything about Libya,’ he says. He lived in a small house with 40 to 50 people, working from 6am until the evening, and food was only provided once a day. He was asked for a ransom for his release, but with no family to pay for him, he thought he would be left to die.

One night, however, he was told not to sleep. Two men with guns came to collect him and brought him to a place where hundreds of people were waiting to board a boat to cross the Mediterranean. With no choice but to board, he did. After a 17-hour journey, they were rescued and brought to Italy.

Musa now volunteers as a translator at the Italian Red Cross health clinic, as he speaks English, Arabic, and a number of local languages from the Gambia. ‘I’m just hoping for the best now. I have seen a lot of bad things. I don’t think anything can make me angry or feel stressed again,’ he says.

Yusuf, 24, and Monday, 36, Nigeria

Yusuf is from Edo state, Nigeria, and arrived in Italy in August 2015. He was born with a congenital malformation, and cannot walk. He made the journey to Europe, which took a total of four months, with his friend Monday, whom he met while travelling from Nigeria to Libya. Whenever the pair had to walk, Monday would carry Yusuf on his back.

Yusuf decided to leave Nigeria because of the difficulties that people with disabilities face there. Both left without telling their families, for fear that they would persuade them not to make the journey.

Yusuf left Nigeria in May, and then spent two weeks in Niger, looking for a driver to take them through the Sahara desert – most refused to carry him because of his disability, believing he would not survive the journey. When he finally persuaded a driver to take him, they drove for four days through the desert, with no food or water. Finally, they reached Libya, where they waited for more than three months for a boat that would take them to Europe. According to Yusuf, ‘Libya is not a country someone should stay.’

Eventually, they boarded a boat and after five hours at sea, they were rescued and brought to Catania port. This was the most difficult part of the journey, he and Monday say. ‘There is no guarantee. As soon as you board the boat, it’s only you and God.’

Both now live in a shared room at Mineo reception centre in Sicily. The Red Cross health clinic there provided Yusuf with a wheelchair for the first time in his life, which he is still getting used to using. Monday is extremely protective of Yusuf, and takes care of him every day.

Maria* and Joel*, both 19, Mali

Maria and Joel are a young couple who hope to get married soon. They left Mali after Maria turned 17, and was at risk of female genital mutilation. Maria initially fled Mali with her father, who refused to let her suffer this traditional practice, and Joel followed soon after.

What awaited them in Libya was even worse. Maria’s father was killed in prison, and Maria, who was frequently alone during the day while men were sent to work, was raped. Desperate, she, Joel and three others escaped from where they were jailed – realising that if they did not leave, they too would die.

They pleaded to be allowed on to a boat headed for Europe, but during the journey it was intercepted by a boat with an armed gang. They took all of the group’s water, food and mobile phones, leaving them with no way to call for help. Five people on their boat drowned. After 14 hours at sea, they were rescued by a German ship and the couple landed in Catania in April 2016.

Maria’s first two weeks in Italy were spent in hospital. Now, she finally feels safe. Joel feels the same: ‘I [felt I] had landed in a country with human rights. No one could arrest me, force me to work, or beat me.’ The couple want to stay in Italy as it is the first place that welcomed them. ‘We have peace now. The most important thing is to have peace.’

Kasim, 25, Somalia

Kasim is from Mogadishu. He arrived in Lampedusa three years ago and has lived in Mineo reception centre since then.

His journey from Somalia took six months. He left to avoid being conscripted into Islamist insurgency group al-Shabaab. His journey took him through Kenya, Sudan, and Libya, where, after three days in the desert, he boarded a boat to cross the Mediterranean. Although there is a large Somali community in Kenya, he says he would not have been safe there because of al-Shabaab’s network.

The crossing to Lampedusa was the most difficult part of his journey. He boarded a boat with 59 people, and was at sea for two days before a ship came to help. Kasim is still waiting for asylum, but says that he feels ‘very, very happy’ to be in Europe. ‘Your life is safe, your health is safe,’ he says. He eventually hopes to go the Netherlands, where his sister lives.

Michael, 28, Eritrea

Michael made the journey to Europe with his wife, Dahab (27) and three children, Benhur (8), Benmet (6) and Lamek (21 months). Michael and his wife fled Eritrea for Sudan with their oldest child in 2009. Hundreds of thousands of Eritreans have fled the country in recent years in order to escape mandatory national service.

The family spent seven years in total in Sudan. However, as the years passed life in Sudan became increasingly difficult. ‘There was not enough freedom,’ he says, especially for Eritrean and Ethiopian people.

The family arrived in Italy in April 2016, after making the journey to Libya and from there crossing the Mediterranean Sea. They were at sea for six and a half hours before an Italian ship came to rescue them. But the hardest part was travelling from Sudan to Libya. The family made the journey in a small car, which did not have enough space for the 35 people travelling in it. Michael had one son on his lap, while his wife and a friend carried the other two children, for the entire journey. The drive took 12 days, without enough food or water. Three of those travelling with them died – two from dehydration, the other when the car crashed. ‘It was very dangerous,’ he says.

Michael and his family are now awaiting a decision on their asylum application. They dream of eventually living in Switzerland, where he has a brother and sister.

Ahmed, 26, Sudan

Ahmed is from Sudan. His journey to Libya took five days. During the trip through the desert, smugglers would mix diesel with the water, to stop people from drinking too much. Upon arriving in Libya, he was kidnapped by Islamic State, and spent two months imprisoned. He would work from morning until night, cleaning and preparing food. Food and water were scarce, and he was frequently beaten. After two months, he managed to escape, but was then arrested by Libyan police. He went on to spend another seven months in prison, during which he worked from morning until evening, and suffered regular beatings.

After his release, Ahmed found work as an electrical technician, and in a month he saved enough money to make the crossing to Italy. He boarded a boat with 120 people – so many that he had to travel with one leg in the water. After five hours, they were rescued by a Spanish boat and taken to Lampedusa, where they landed in January 2016.

‘There are no human rights in Libya,’ he says. From Lampedusa, Ahmed was taken to Mineo, where he now lives and is waiting to hear about his asylum claim. ‘They have good rules in this country.’ Ahmed eventually hopes to come to the UK, where he has a cousin.

More than 120,000 migrants have arrived across the Mediterranean into Italy this year. Italy turned down around 60% of of asylum applications made in the country in 2015 but numbers of applications are low because many people want to reach countries such as Germany, Sweden or the UK. Conditions for migrants in Italy are often very poor, with many sleeping on the streets or in reception centres miles from the nearest town.

- Names changed to protect identities